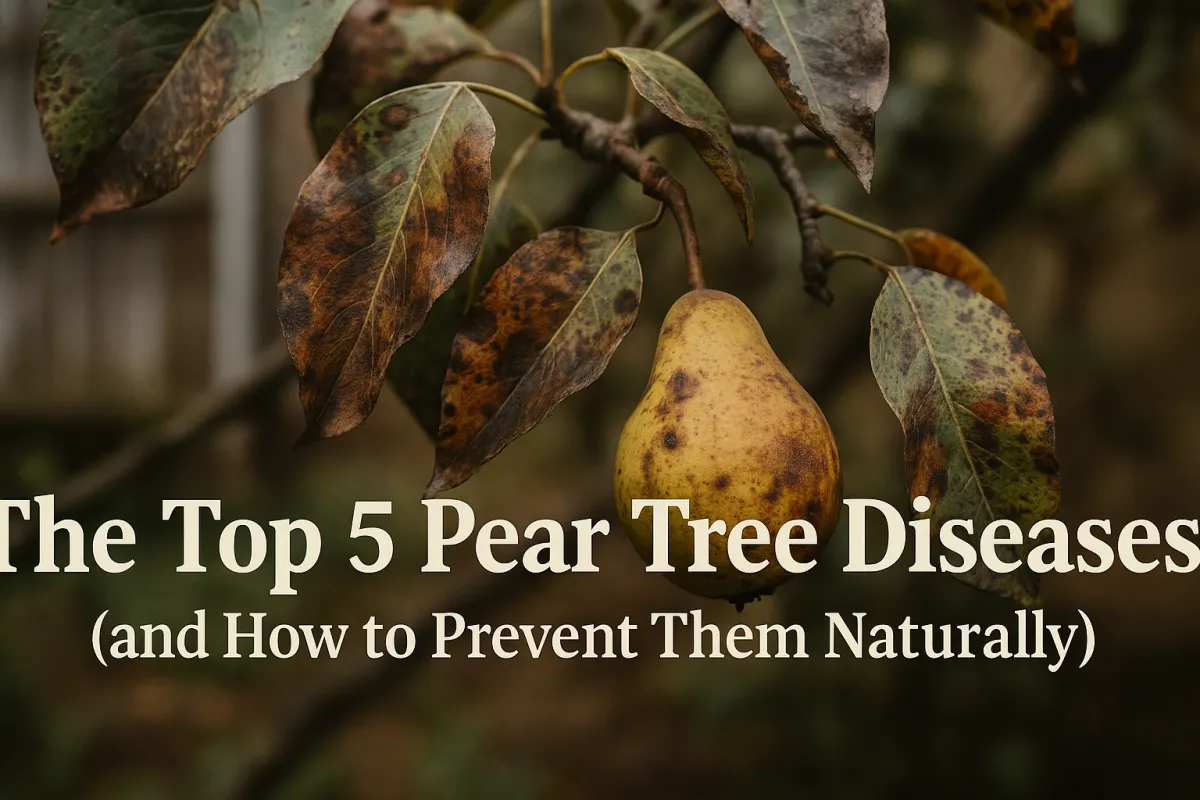

The Top 5 Pear Tree Diseases: Identification & Natural Prevention Guide

The Top 5 Pear Tree Diseases: Identification & Natural Prevention Guide

Lessons From Grandpa’s Pear Trees

1. Fire Blight (The Most Destructive Pear Tree Disease)

2. Pear Scab (The Fungus Behind Black Spots and Leaf Curl)

3. Rust (The Spore-Sharing Disease Between Pears and Cedars)

4. Powdery Mildew (The White Film That Weakens Growth)

5. Crown and Root Rot (The Hidden Killer in Wet Soil)

Honorable Mention: Sooty Blotch & Flyspeck

Restoring Vigor After Infection

Looking for more professional guidance & homesteading resources?

Lessons From Grandpa’s Pear Trees

My grandpa’s pear trees were as dependable as the seasons — sturdy trunks, strong branches, steady fruit every summer. Then one year, a spring storm ripped through and split a few limbs. We patched the wounds and figured they’d heal.

Weeks later, the new shoots turned black and curled. Leaves wilted, and the bark around the breaks went dark. That’s when we realized the storm had opened the door to fire blight — a bacterial disease that takes hold fast when weather wounds the tree.

It was a simple reminder: pear trees can handle a lot, but they can’t shrug off infection. Most problems start when stress or damage gives disease a foothold. And once you’ve seen it happen, you start paying closer attention — to every leaf spot, every curl, every sign that something’s off.

That’s why it pays to know the top pear tree diseases before they show up in your orchard. The more you understand what’s coming, the easier it is to prevent it.

Why Pear Trees Get Sick

If you grow pear trees, you’ll eventually run into trouble. Humid springs, poor airflow, or lingering moisture on leaves can turn a healthy orchard into a petri dish for fungus and bacterial infections. Zones 5 through 8 are especially prone to disease pressure, where warm rain and late frost keep trees under stress.

In places like the Midwest and East, where cedars and junipers are common, rust spreads fast between hosts. In the drier West, growers fight different battles — powdery mildew and nutrient stress from long dry spells.

The point is simple: disease thrives where trees are stressed. Poor drainage, overwatering, heavy pruning, or even fertilizer imbalances can all weaken a pear’s natural defenses.

Keeping a pear tree healthy means paying attention to what the environment’s telling you — sunlight, air movement, and moisture levels matter as much as the soil beneath it. If you manage those right, most pear tree diseases never get the upper hand.

1. Fire Blight (The Most Destructive Pear Tree Disease)

If there’s one disease every pear grower should know by sight, it’s fire blight. Caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, it can sweep through an orchard in a single wet spring. Once established, it kills young shoots fast and can destroy whole branches if ignored.

How to Identify Fire Blight

Blackened, scorched-looking shoots — they droop like burnt matchsticks.

Shepherd’s crook tips on new growth.

Blossoms that turn brown and shrivel instead of setting fruit.

In severe cases, oozing bacterial sap at branch wounds.

For a deeper look at the biology and management of Erwinia amylovora, check out the WSU extension’s Fire Blight guide — it’s one of the most trusted resources for growers.

How to Prevent Fire Blight Naturally

Prune out infected wood at least 8–12 inches below visible damage. Always sterilize pruning tools between cuts.

When you’re pruning diseased wood, a reliable tool like Fiskars 28" Loppers makes the difference — clean cuts heal faster and slow pathogen entry.

Never prune during wet weather. That’s when bacteria spread most easily.

Choose resistant cultivars such as Harrow Delight, Magness, or Warren.

Apply copper sprays during bloom in high-pressure years for organic protection.

Note: Copper is approved for organic use but can be toxic to beneficial insects if overused. Follow label instructions carefully.

Keep nitrogen levels balanced — overfertilized trees push soft growth that blight loves.

The USDA’s long-running pear breeding initiatives, detailed in Frontiers in Plant Science, show how resistance to fire blight and other diseases has been a central goal for decades.

Pro Tip: Think of fire blight as a wound infection — not just a leaf problem. The cleaner your cuts and the better your timing, the faster your tree rebounds.

2. Pear Scab (The Fungus Behind Black Spots and Leaf Curl)

Pear scab is one of the most common fungal diseases affecting pear trees, caused by Venturia pirina. It thrives in cool, wet weather and spreads fast when fallen leaves aren’t cleared away. Left unchecked, it can deform fruit, weaken shoots, and set your orchard back an entire season.

How to Identify Pear Scab

Dark, velvety spots on leaves or young fruit.

Olive-brown lesions that cause curling or early leaf drop.

Repeated infections can leave misshapen, cracked fruit that doesn’t store well.

The UC IPM program’s Apple & Pear Scab Pest Notes are a gold-standard reference for spotting and managing scab in home and commercial orchards.

How to Prevent Pear Scab Naturally

Practice sanitation first. Rake and remove fallen leaves and mummified fruit each fall to cut off the fungus’s overwintering sites.

Improve airflow. Prune overcrowded branches so sunlight and wind can dry foliage quickly.

In high-pressure years, apply organic fungicidal sprays early in the growing season.

For a ready-to-use, organic-approved copper spray, many homesteaders rely on Earth's Ally Natural Fungicide Concentrate to provide that protective barrier against fungal spores and bacterial infection.

Keep the area around the trunk free of debris to limit fungal spore buildup.

Grandpa’s Tip: “Keep your orchard floor clean — a dirty bed breeds trouble.”

Pro Tip: Even one skipped cleanup can restart the scab cycle. Treat sanitation as part of your harvest, not an afterthought.

3. Rust (The Spore-Sharing Disease Between Pears and Cedars)

Pear rust is a fungal disease that relies on two hosts — usually pear trees and junipers or cedars — to complete its life cycle. The fungus, often Gymnosporangium globosum (Hawthorn Rust) or G. juniperi-virginianae (Cedar-Apple Rust) in North America, spreads by windblown spores, moving back and forth between species each season. Once it finds a weak spot, it disfigures leaves, reduces vigor, and makes trees more vulnerable to other infections.

How to Identify Rust on Pear Trees

Orange or rust-colored spots on the tops of leaves.

Swollen, distorted patches or growths on the undersides.

Premature leaf drop or weakened buds late in the season.

Often seen when junipers, red cedars, or ornamental shrubs grown nearby.

How to Prevent Rust Naturally

Remove alternate hosts like cedars and junipers within a few hundred feet of your orchard if possible.

Space your trees so air and sunlight reach every canopy layer — moisture fuels rust spores.

Choose resistant cultivars where rust pressure is high.

If removing cedars isn’t an option, prune out infected growth early and dispose of it far from your orchard.

Keep trees well-fed but not overfertilized; strong tissue resists fungal invasion better.

Region Note: Rust hits hardest in humid regions like the Midwest and Eastern U.S., where cedars and pear trees often share the same airspace.

Pro Tip: If your pear leaves look painted with orange freckles in late spring, don’t ignore it — that’s the early sign rust is settling in for the season.

4. Powdery Mildew (The White Film That Weakens Growth)

Powdery mildew is a common fungal disease that thrives when days are warm and nights are cool — exactly the kind of weather most pear trees love. The fungus coats leaves and shoots in a fine white film, cutting off sunlight and slowing growth. If ignored, it weakens the tree’s vigor and reduces next year’s fruit set.

How to Identify Powdery Mildew

White, powdery coating on leaves, buds, or shoots.

Twisted or stunted new growth.

Infected buds may fail to open, and fruit can develop a dull, rough skin.

How to Prevent Powdery Mildew Naturally

Space trees generously. Crowded canopies trap humidity and give spores a foothold.

Prune for airflow and light. A well-shaped tree dries faster after dew or rain.

Use organic sprays like neem oil, sulfur, or potassium bicarbonate when mildew first appears.

To tackle both fungal pests and insect pressure in one go, many homesteaders rely on a trusted organic option like Harris Neem Oil — it helps prevent mildew, rust, leaf-spots and also suppresses pests that stress pear trees.

Avoid overfertilizing with nitrogen; soft, lush growth is more prone to infection.

Water early in the day so leaves dry before nightfall.

Pro Tip: Don’t panic at the first sign of mildew. Light infections rarely kill — but they’re a warning your orchard needs more breathing room.

5. Crown and Root Rot (The Hidden Killer in Wet Soil)

When pear trees start yellowing, stunting, or collapsing without an obvious cause, the culprit is often crown or root rot. This fungal disease thrives in soggy, poorly drained soil where oxygen is limited and roots stay waterlogged. The pathogens — often Phytophthora species — infect the tree at the base, rotting tissue until it can no longer pull water or nutrients.

How to Identify Crown and Root Rot

Stunted growth and pale, yellowing leaves despite adequate fertilizer.

Sudden wilting or dieback during warm weather.

Dark, mushy bark at the base of the trunk (the crown).

A sour, earthy smell near the soil line — a sign of rotting roots.

How to Prevent Root Rot Naturally

Plant in well-drained soil. If water pools after rain, raise the bed or build a berm.

Avoid overwatering. Pear trees prefer deep, infrequent watering over constant moisture.

Mulch wisely: keep mulch a few inches away from the trunk to prevent trapped moisture.

Improve drainage. Use gravel, tile, or shallow trenches to redirect standing water.

Select tolerant rootstocks if your area is prone to flooding or heavy clay. The rootstock choice is a critical, one-time preventative measure: Look for OHxF 87 or OHxF 97 for superior resistance to fire blight and good tolerance to heavy soils. Avoid highly vigorous, blight-susceptible rootstocks like Bartlett Seedling.

Region Note: Growers in low-lying or clay-heavy soils — especially in the Midwest — are most at risk.

Pro Tip: Once crown rot sets in, there’s rarely saving the tree. Prevention is the only real cure — control water, and you control the disease.

Honorable Mention: Sooty Blotch & Flyspeck

These are two distinct but often co-occurring cosmetic fungal diseases that thrive in long periods of high summer humidity. They attack the fruit cuticle (skin) late in the season, reducing marketability but rarely harming the tree's overall health.

How to Identify Sooty Blotch & Flyspeck

Sooty Blotch: Appears as olive-green to black, dull, smoky, or sooty patches on the fruit skin that can be rubbed off easily.

Flyspeck: Appears as clusters of tiny, superficial, shiny black dots that look like fly excrement, often grouped together but not merging.

How to Prevent Sooty Blotch & Flyspeck Naturally

Improve Airflow: The primary defense is aggressive summer pruning to open up the canopy, allowing sunlight and wind to dry the fruit surface quickly.

Sanitation: Remove nearby weeds, wild berries (like brambles), and brush piles, as these can harbor the fungi.

Late-Season Coverage: In high-pressure years, apply organic sprays like lime sulfur or copper in mid-to-late summer to provide a protective barrier until harvest.

Restoring Vigor After Infection

A severe disease event is a trauma to the tree. To help it bounce back naturally:

Focus on Soil Health: Apply compost tea or well-aged compost around the drip line in spring. This boosts microbial life, making nutrients more available.

Avoid Nitrogen Spikes: Stick to balanced, slow-release organic fertilizers and aged compost to prevent the soft, sappy growth that attracts Fire Blight.

Optimize pH: Pear trees prefer slightly acidic soil (pH 6.0–6.5). Use peat moss or elemental sulfur judiciously to drop the pH if your soil test shows it’s too high.

Printable Tool

Save the Pear Tree Problem Solver — a quick one-page guide showing symptoms and the exact prevention steps for each of these diseases. Print it, hang it in the shed, and use it as a weekly orchard walk checklist.

Pear Tree Health Cheat Sheet

Quick Identification & Natural Prevention Guide

1. Fire Blight — The Burnt Tip Disease

Cause: Bacteria (Erwinia amylovora)

Looks Like:

Blackened, scorched shoots and “shepherd’s crook” tips

Blossoms that brown and shrivel

Natural Prevention:Prune 8–12" below infection; disinfect tools

Avoid pruning in wet weather

Apply copper spray during bloom

Use resistant varieties (Harrow Delight, Magness, Warren)

2. Pear Scab — The Black Spot Fungus

Cause: Fungus (Venturia pirina)

Looks Like:

Dark, velvety spots on fruit and leaves

Olive-brown lesions that curl leaves

Natural Prevention:Rake and remove fallen leaves and fruit

Prune for airflow and sunlight

Apply organic fungicide in early season

3. Rust — The Orange Freckle Fungus

Cause: Fungus (Gymnosporangium sabinae)

Looks Like:

Orange or rust-colored leaf spots

Distorted growth or leaf drop

Natural Prevention:Remove nearby cedars/junipers

Space trees for airflow

Choose resistant cultivars

Prune infected growth early

4. Powdery Mildew — The White Film

Cause: Fungal spores thriving in humidity

Looks Like:

White coating on leaves, buds, shoots

Twisted or stunted new growth

Natural Prevention:Prune for light and airflow

Apply neem, sulfur, or potassium bicarbonate spray

Avoid excess nitrogen fertilizer

5. Crown & Root Rot — The Silent Killer

Cause: Waterborne fungi (Phytophthora species)

Looks Like:

Yellow leaves, stunted growth, dieback

Dark, soft bark near trunk base

Natural Prevention:Plant in well-drained soil or raised beds

Keep mulch off trunk

Fix drainage or redirect standing water

Seasonal Reminders

✅ Spring: Watch for blight during bloom; prune cleanly.

✅ Summer: Check undersides of leaves for rust or mildew.

✅ Fall: Clean up debris and fallen leaves to stop fungal spread.

✅ Winter: Inspect pruning wounds and plan next year’s maintenance.

Stay Ahead and Bear Fruit

Every pear tree faces pressure — from fungus, bacteria, or the weather itself. But growers who walk their orchard, notice the small changes, and act early rarely lose a tree. Disease almost always starts small: a black tip here, a spot there. The key is catching it before it spreads.

The discipline of the orchard holds a simple, powerful lesson, one that even scripture reflects: John 15:2 (NKJV) says, “Every branch in Me that does not bear fruit He takes away; and every branch that bears fruit He prunes, that it may bear more fruit.”

Pruning feels harsh — cutting back what looks fine from the outside — but it’s how both trees and people stay healthy. Discipline isn’t destruction; it’s preparation for more growth.

Keep your tools clean, your soil well-drained, and your pruning deliberate. Do that, and your orchard — and your life — will both bear better fruit.

Ready to Act? Download the free problem solver JPG and share this guide with a fellow grower who needs it!

Pear Tree Disease FAQ

What are the most common pear tree diseases?

The top five are fire blight, pear scab, rust, powdery mildew, and crown or root rot. Each targets different parts of the tree — from shoots and blossoms to roots and bark — but all thrive in humid, poorly managed conditions.

How can I prevent pear tree diseases naturally?

Most prevention comes down to good orchard management:

Prune for airflow and remove dead or infected branches.

Clean up fallen leaves and fruit to stop fungal spores from overwintering.

Avoid overwatering or letting soil stay soggy.

Use organic sprays like copper or neem oil judiciously during high-risk periods.

Healthy trees resist infection far better than stressed ones — prevention is always easier than cure.

Can I treat fire blight without chemicals?

Yes, but timing matters. Prune infected wood 8–12 inches below visible damage, disinfect tools between cuts, and avoid pruning during wet weather. Copper sprays (organic-approved) can help suppress bacteria if applied early in bloom, but sanitation and timing do most of the work.

Why do my pear leaves turn orange in summer?

That’s usually pear rust, a fungus spread between cedars or junipers and pear trees. Spores travel by wind, infecting leaves in warm, humid weather. Remove nearby junipers if possible, prune affected leaves, and keep trees spaced for airflow.

What causes black spots on pear fruit?

Pear scab is the main cause. It creates dark, velvety lesions that spread in wet, cool conditions. Rake fallen leaves in fall, prune for sunlight, and use an early-season organic fungicide if you’ve had scab before.

How do I know if my pear tree has root rot?

Look for yellowing leaves, slow growth, and soft, dark bark near the soil line. Trees may wilt suddenly in heat even when watered. Root rot thrives in poor drainage, so improving soil structure and water flow is critical to prevention.

When is the best time to prune pear trees to prevent disease?

Late winter or early spring — before buds break — is ideal. Pruning in dry weather limits infection risk. In summer, light touch-up pruning for airflow helps keep leaves dry and fungus-free.

What are the best organic treatments for pear tree fungus?

Copper fungicide (used sparingly in bloom)

Neem oil (effective against mildew and some leaf spots)

Sulfur or potassium bicarbonate sprays (for mildew control)

Always pair treatments with good sanitation and drainage for lasting results.

Can weather cause pear tree diseases?

Yes. Storm injuries, frost cracks, and prolonged humidity all stress pear trees, making them more vulnerable. Even a broken branch from a storm can invite fire blight through open wounds. Healthy trees recover quickly — stressed ones don’t.

How can I tell if a pear tree is beyond saving?

If the main trunk is split, bark at the crown is soft or dark, or over half the canopy is dead, the tree is usually past recovery. In those cases, removal prevents the disease from spreading to nearby trees.

Video Summary of this issue:

As always, the tools and supplies I mention are the same ones I rely on here at The Grounded Homestead. Some are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission—at no extra cost to you—but every recommendation is based on real use and trust.

Looking for more professional guidance & homesteading resources?

Explore our trusted guides to learn more about growing healthy food, managing your land, and building lasting systems for your homestead. Whether you're looking for planting tips, seasonal checklists, or natural solutions that actually work—we’ve got you covered.

Start with these helpful reads:

Everything to know about Strawberries:

Start with Strawberries: Ground Your Garden with Fruit that Grows Back

6 Common Strawberry Plant Diseases and How to Treat Them Naturally

The 6 Pests That Wreck Strawberry Crops—and How to Beat Them Naturally

Beyond Straw: Choosing the Right Mulch for Every Strawberry Bed

Runner Management 101: Multiply Your Strawberry Patch with Purpose

Frost, Flood, and Fungus: Protecting Strawberries in Extreme Weather

The Best Strawberry Varieties for Continuous Summer Harvests

Top 14 Practical Uses for Fresh Strawberries (Beyond Jam)

Start a U-Pick Strawberry Business (Even on 1 Acre)

How to Fertilize Strawberries for Yield, Flavor, and Runner Control

Strawberries in Small Spaces: Balcony, Border, and Vertical Growing Techniques

Wild Strawberries vs. Cultivated: Should You Grow Fragaria vesca?

The Complete Guide to Propagating Strawberries: Growing Strawberries from Seed

How to Integrate Strawberries Into a Permaculture Garden

How to build a low-maintenance 4-bed strawberry system’

Everything to know about Raspberries:

Start with Canes: How to Plant Raspberries for a Lifetime of Fruit

Raspberry Care 101: From Cane to Crop Without the Fuss

Build a Raspberry Trellis That Lasts: Sturdy DIY Designs for Any Backyard

When and How to Cut Back Raspberries: The Right Way to Prune Summer and Fall Types

Raspberry Troubleshooting Guide: Yellow Leaves, No Fruit, and Cane Dieback

Raspberry Pest Guide: What’s Bugging Your Patch (and What to Do About It)

Everything to know about Lettuce:

Lettuce 101: How to Grow Crisp, Clean Greens Anywhere

The Lettuce Succession Plan: How to Get a Salad Every Week from Spring to Fall

Top 5 Lettuce Diseases—and What to Do When They Show Up

Top 5 Lettuce Mistakes New Gardeners Make

Top 5 Lettuce Pests—And How to Keep Them Out Naturally

Everything to know about Tomatoes:

Tomatoes 101: How to Grow Strong, Productive Plants from Seed to Sauce

Tomato Feeding Guide: What to Add, When to Add It, & How to Avoid Overdoing It

The Top 5 Tomato Problems—And How to Fix Them Before They Ruin Your Harvest

Pruning Tomatoes: When, Why, and How to Do It Without Hurting Your Plants

The Top 5 Mistakes First-Time Tomato Growers Make (And How to Avoid Them)

Everything to know about Kale:

The Top 5 Kale Pests — How to Protect Kale from Bugs Organically

How to Harvest Kale the Right Way (So It Keeps on Giving)

Kale 101: A No-Fuss Guide to Growing Tough, Nutritious Greens

What to Do When Kale Looks Rough: Yellowing, Holes, or Curling Leaves

Kale Varieties Demystified: What to Grow and Why It Matters

How to Keep Kale from Getting Bitter (Even in Warmer Months)

Everything to know about Green Beans:

Green Beans 101: Planting, Caring, and Harvesting for Steady Summer Yields

The Top 5 Green Bean Problems—and How to Fix Them Naturally

Succession Planting Green Beans for a Full Summer Harvest

The Top 5 Pests That Wreck Green Beans—And What to Do About Them

Bush vs. Pole Beans: Which Is Better for Your Garden?

Everything to know about Zucchini

Zucchini & Summer Squash 101: Planting, Caring, and Harvesting for Massive Yields

The Top 5 Zucchini Problems—And How to Solve Them Naturally

Companion Planting with Zucchini: What Helps and What Hurts

Harvesting Zucchini the Right Way (and Why Size Matters)

The Squash Vine Borer Survival Guide

Everything to know about Watermelon

How to Tell When a Watermelon is Ripe (Without Guesswork)

Watermelon 101: How to Grow Sweet, Juicy Melons from Seed to Slice

The Top 5 Watermelon Growing Problems—and How to Fix Them Naturally

The Top 5 Pests and Diseases That Target Watermelon

Companion Planting with Watermelon: What to Grow Nearby (and What to Avoid)

Everything to know about Radish

Radish Growing 101: From Seed to Crunch Without the Guesswork

When and How to Plant Radishes for Crisp, Flavorful Roots

The Top 5 Radish Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

How to Harvest Radishes at the Perfect Time (and Avoid Woody Roots)

The Top 5 Radish Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Everything to know about Blueberries

Feeding Blueberries Naturally: The Right Fertilizer at the Right Time

The Top 5 Blueberry Pests (and How to Stop Them Without Chemicals)

Why Your Blueberry Bush Isn’t Producing Fruit (and How to Fix It)

Blueberry Care 101: From Bush to Bowl Without the Guesswork

The Top 5 Blueberry Diseases (and How to Beat Them Naturally)

Everything to know about Pear Trees

The Top 5 Pear Tree Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Pear Tree Care 101: From Planting to Picking

When and How to Harvest Pears for the Best Flavor

The Top 5 Pear Tree Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

Pruning Pear Trees Without Hurting Next Year’s Crop

Everything to know about Apple Trees

The Top 5 Apple Tree Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

When and How to Harvest Apples for Peak Flavor

Why Your Apple Tree Isn’t Producing Fruit (and How to Fix It)

The Top 5 Apple Tree Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

Apple Tree Care 101: From Planting to Picking Without the Guesswork

Everything to know about Onions

The Top 5 Onion Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Onions 101: From Seed to Storage Without the Guesswork

When and How to Plant Onions for Big, Healthy Bulbs

The Top 5 Onion Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

Why Your Onions Won’t Bulb (and How to Fix It)

How to Grow Onions: A Complete Harvest Guide

Everything to know about Garlic

The Top 5 Garlic Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Garlic Growing 101: From Clove to Harvest Without the Guesswork

When and How to Plant Garlic for Big Bulbs

The Top 5 Garlic Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

The Right Way to Feed Garlic for Bigger, Healthier Bulbs

Everything to know about Pumpkins

Why Your Pumpkins Aren’t Setting Fruit (and What to Do About It)

Pumpkins & Squash 101: From Seed to Storage

When and How to Harvest Pumpkins & Squash Without Ruining the Fruit

The Top 5 Pumpkin & Squash Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

The Top 5 Pumpkin & Squash Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Everything to know about Cantaloupe

Why Your Cantaloupe Won’t Ripen (and What to Do About It)

When and How to Harvest Cantaloupe (So It’s Sweet, Not Bland)

Cantaloupe 101: From Seed to Sweet Slice

The Top 5 Cantaloupe Pests (and How to Stop Them Organically)

The Top 5 Cantaloupe Diseases (and How to Prevent Them Naturally)

Other Offerings:

The Summer Garden Reset: What to Do After Your First Harvest

How to Keep a Backyard Garden Alive in 90° Heat (Without Daily Watering)

Facebook

Instagram

X

Youtube